Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) policies on the detention of undocumented immigrants and those claiming refugee status have recently come under fire from the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights’ Working Group on Arbitrary Detentions and major Canadian newspapers including the Toronto Star and the Times Colonist of Victoria, British Columbia.

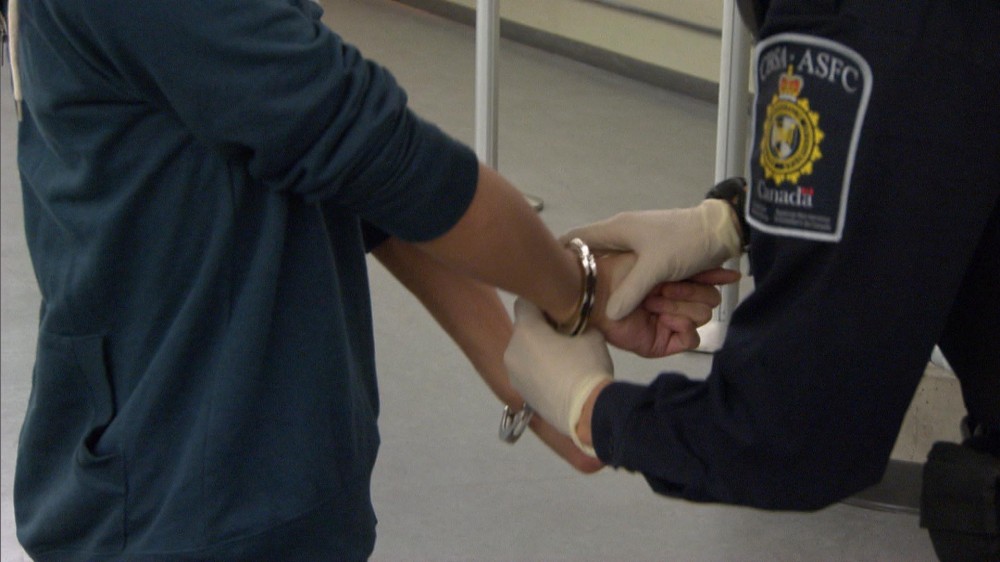

The agency’s ability to question, hold, and expel prospective immigrants and asylum applicants was drastically expanded in 2012 under the Protecting Canada’s Immigration System Act. The act, promoted as a way to expedite the processing of refugee protection claims, allows the Minister of Citizenship and Immigration to unilaterally designate an arrival in Canada as an irregular arrival. Borders Services Officers are mandated to detain designated individuals over 16 years of age when they arrive in Canada, and those who become designated after having entered the country are subject to warrantless arrest and detention.

Detentions are reviewed by the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (IRB) within 48 hours, but migrants who are determined to be designated individuals, pose a risk of flight or a threat to public safety, or traveling on false documents may then have to wait as long as a year before their next hearing. Most cases don’t take anywhere near that long – the average length of detention is less than a month – but some people have been held for years.

One of the most notorious cases is that of an African man calling himself Victor Vinnetou who came to Canada in 1988 and has been in detention since his immigration-related arrest in 2004. (He’s believed by some to be Mbuyisa Makhubo, a vanished hero of the South African anti-apartheid struggle.) Another man, Michael Mvogo, has been held since 2006; he is said to have connections to Cameroon, Guinea, Haiti, Spain, and the United States, but his true nationality in unclear and none of those countries have agreed to accept him.

Such lengthy detentions put Canada at odds with most other Western democracies. The U.S., U.K., and most E.U. countries release immigration detainees awaiting deportation after no more than 180 days, more commonly after 90 days. Perhaps only Australia’s policy of mandatory detention is harsher.

And while most migrants only spend a few weeks in detention, the conditions in which they’re held are so poor that they constitute an embarrassing blot on Canada’s human rights record, critics say. For one thing, almost half are kept in provincial jails, many in maximum security facilities, even though international law prohibits housing detainees who haven’t been charged with a crime alongside convicts.

Nor are the CBSA’s own holding facilities necessarily any better than prison. It’s hard to say for sure because the agency seems intent on keeping them as secret as possible. Detainees are not allowed to have any outside contact, and even their lawyers cannot talk to them inside their cells. There is also no oversight mechanism, and thus no way of finding out what went wrong when an incident occurs. Even worse, there’s no way of knowing that an incident has occurred until the CBSA decides to disclose it. For example, when Lucia Vega Jiménez of Mexico hanged herself at the Vancouver Immigration Holding Centre last December, it took over a month for the agency to release the news.

Detention isn’t the only area where the CBSA has been getting negative reviews. Its aggressive immigration sweeps and raids are deeply unpopular with immigrant communities and civil liberties groups. Last month 21 people were arrested in Toronto after failing to produce proof of legal immigration status during “vehicle safety inspections”. While the Vancouver construction site raid broadcast on the National Geographic Channel reality show Border Security: Canada’s Front Line last year generated a lot of complaints, that certainly doesn’t seem to have changed the agency’s approach.

The CBSA is a relatively new agency, formed in 2003 to combine immigration, customs, and agricultural inspection functions for enhanced security following the 2001 Smart Border Declaration with the U.S. To some extent this move has served its purpose by allowing intelligence to be shared more efficiently within the agency. But the consolidation has also had the effect of making the view from outside considerably more opaque.

There’s no question that the CBSA has a vital role in upholding Canadian law and national security, but Canadian humanitarian values are also important, and the increasing level of criticism from a variety of widely-respected sources suggests that it’s time for the Harper government to initiate a review of how well the agency is carrying out its mission in that regard.

Payment

Payment  My Account

My Account